Khalid Jabara And What It's Like Being An Arab-American

A few days ago, Lebanon was rocked by the saddening news of

a Lebanese-American’s murder in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Khalid Jabara was 37 years old

when he was shot to his death by neighbor Stanley Majors.

Majors had a documented history of racist hate crimes against the

Jabara family, who in the 1980s had transplanted from Lebanon and made their

home in the southern state. Foul language – expressions like “dirty Arabs,” “filthy

Lebanese,” and “Mooslims” – as well as running over Khalid’s mother in

September 2015 point to a neurotic psychopath who should have been thrown behind

bars. The truth is he served six months in jail for last year’s mow-down and

was released without parole or house arrest in March.

I won’t delve deeper into the details of the crime, because

those can be found in any news publication, from CNN

to The

Guardian. This piece is about the empathy I feel with the Jabara family,

whose loss can never be forgotten nor redeemed.

Having grown up in the US, particularly in Southern

California, I can somewhat testify to how tricky it is to pass unnoticed as an

Arab-American. I spent my childhood fending off pointed questions like “Where

are you from?” and “No, where are you really from?” whenever I answered I was a

California native.

| Anyone remember the movie "Mean Girls"? Yes, bullying based on differences does exist! |

Assuring curious onlookers that I was born and raised in the

Golden State never sufficed. They immediately sensed I was different. Wavy

brown locks, brown eyes and my distinctively Mediterranean look betrayed me as

a foreigner, even though by definition I am not. If my spoken and written

English are indication alone of my “Americanness,” I put all these

people to shame, I’d think.

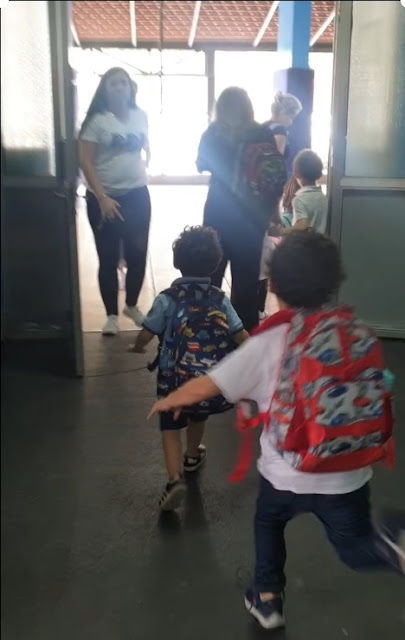

|

| Me as a child |

Growing up, I detested being singled out. Children have a

way of being unjustly critical, of banding up and ostracizing those who don’t

blend in with their identity. I didn't fit nearly inside the perimeter of those

narrow boxes.

My pita bread sandwiches at lunchtime were a dead giveaway,

as was my inability to attend sleepover parties – my parents weren’t as

accommodating as those of my American friends. I was fluent in Arabic, but I

avoided speaking it in public for fear of becoming the

object of disdain.

| Photo credit: http://worldartsme.com/ |

Did I experience any alarming racism in the US? I still

recall how my brother’s freshman chemistry professor brashly attacked him after

the events of 9/11. “Look at what your people have done to my people,” she

uttered. He was speechless. Though his grades easily landed him

an “A,” she marked “B+” on his transcript, and he had to escalate the issue with

the dean to have the inaccuracy revoked.

Whenever I was cornered into admitting my “Lebaneseness,” I

was frustrated that no one could pin the country on a map. I’d mention the

Middle East, after which they wanted to clarify whether we rode camels and traversed

sand dunes.

Moving to Lebanon five years ago was for the most part natural. Here, I can identify with the culture and

value system. Sure, my English accent reveals I wasn’t born in these parts, but

that’s never proved to be a drawback. In fact, it draws favor and admiration

from my peers. They’re tickled I chose Lebanon over any Western bastion, as though

they need me to appraise the value of the Lebanese experience.

It’s true that some Lebanese have trouble stomaching why anyone

with a second nationality would ever waste a minute living in our backward

dystopia. They don’t know what it’s like to be scoped from head to

toe; to be set apart for not blending in with a nonexistent archetype;

to be frisked every time they step foot inside an airport and are searched

overtly before questioning eyes.

They’ve never been in my shoes, or in the shoes of Khalid

Jabara and his family members, for that matter.

Rest in peace, Khalid. May the memory of your plight live

on, and may this world find peace in our time.

|

| Khalid Jabara, the victim of racism |

Awesome post! We live in disgusting times!

ReplyDeleteTruly despicable. Thanks for reading, Serene!

DeleteThank you for this reflective post. I, too, lived in Southern California during most of my time in the States. However, the general feeling I had was positive. I would be hard pressed to think of an experience as unfortunate as the one your brother had. Perhaps it was because you lived in the conservative part of So Cal (no?); while I lived in a town that was a center for hippies in their heyday, allowed rent control, and was so friendly to the homeless that the cops would not (or could not) arrest them for public urination, an illegal act in California. That town was dubbed the People’s Republic of Santa Monica.

DeleteOklahoma, as most of us know, is a state as redneck as they come. A Santa Monican judge (or office of parole) would never grant an early release for a similar crime as the one committed against Khaled’s mother. A Santa Monican court would have seriously considered Stanley Majors’ first act a hate crime, punishable by a much longer sentence than he received.

So, the place (and the people living in it) does matter, is what I am trying to say. Even the most narcissistic or blue-eyed Santa Monican would be just as happy with a Middle Eastern doctor as with an Anglo-Saxon. He would cherish the opportunity to go over to his, say, Lebanese neighbor’s house, not to quarrel with or shoot him, but to eat his hummus & tabbouleh.

Unfortunately, Khaled Jabara, because of the despicable act of Stanley Major, will never have the opportunity to live in a place like Santa Monica or the countless other friendly places in America, or to come back to Lebanon, for that matter.